Study identifies link between fluctuations in global gold price and survival rates among baby girls

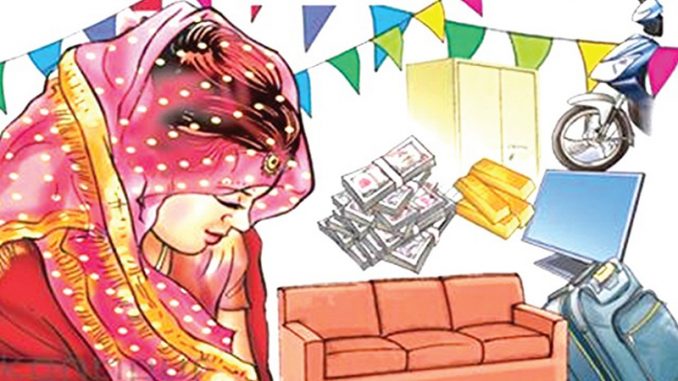

Girls born in India when the global gold price is increasing are more likely to be aborted, die in the first month of life or suffer from stunted growth, researchers have found.

A study analysed birth cohort data over a 35-year period alongside monthly variations in the global price of gold, a key element of dowries paid by a bride’s family. It found that in months when the gold price went up, fewer baby girls survived the first month of life.

Parents were responding to the rising cost of dowries by reducing the chances of a baby girl surviving, according to the research, which concluded that dowries are a significant contributor to the country’s skewed gender ratio.

The analysis, which included a representative sample of more than 100,000 births, found inflated gold prices correlated with improved survival chance for boys relative to girls.

Between 1972 and 1985, a 1% increase in gold prices is estimated to have caused an additional 13,000 neonatal deaths among girls each year. This estimation is based on data from 1980, when there were roughly 30 million births in India.

Women born in months when the gold price was inflated were also shorter in adulthood, suggesting their growth was stunted because they had been deprived of key nutrients early in life. This was not observed for boys born at times of inflated gold prices.

Behaviour patterns appeared to change after 1985, when ultrasound scans, which show the sex of a foetus, became widely available, said Sonia Bhalotra, professor of economics at the University of Essex, who conducted the study.

“We find that parents are consistently ‘eliminating’ girls early in life, but the pattern is that this is done soon after birth before 1985, and while the girl is in the womb after 1985,” said Bhalotra.

After 1985, a 1% rise in the global price of gold led to an extra 33,000 “missing” female births each year. This estimation is based on data for 1995, when there were roughly 27 million births in India.

Tests to determine a foetus’ sex are illegal in India, but it is common for families to pay doctors for this service. “There’s always an underground abortion clinic that will do it for you,” Bhalotra said.

Though dowries have been illegal since 1961, they remain widespread in India, where they place a severe financial burden on families. Across south Asia, dowries can cost about six times the average annual household income. The study shows that dowry payments rise almost proportionally with gold prices.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 7,634 women died in 2015– 20 every day – due to dowry harassment. This includes women who were either murdered or felt compelled to take their own lives.

Census figures for 2011 show a skewed gender ratio: there were 914 girls to every 1,000 boys for children up to the age of six. In some northern states the ratio dropped below 850.

In 2015, the government launched a national campaign to tackle the preference for boys, promising stronger enforcement of laws that forbid sex-selective abortion and diagnostic techniques used for female foeticide, in addition to promoting girls’ schooling.

Dowry prohibition isn’t working, partly because the dowry transfer between families is so hard to monitor, said Bhalotra. Giving women economic independence and changing property rights may gradually help to weaken the practice, she added.

“[Parents can] say: ‘I’m not giving you a dowry because she has a job as good as the man’s,’” said Bhalotra.

“It is much harder to change social norms when people are older, but experimental research suggests that gender sensitisation in primary and secondary school may modify attitudes.”

Some Indian states have explored other ways to incentivise families to have daughters, such as giving each baby girl a fund that matures when she turns 18.

While progress has been made in improving access to education for girls, said Bhalotra, work participation rates remain low, especially for poorer women.

Source: The Guardian

Leave a Reply