By Sanjay Vijayakumar

Top 1% of earners captured less than 21% of total income in the 1930s, which dropped to 6% in the ’80s and has risen to 22% now, says economist.

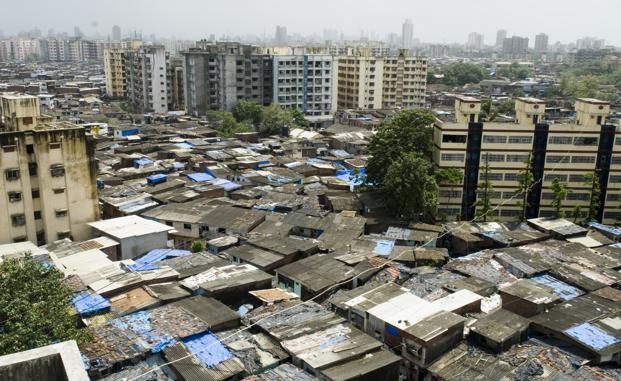

According to a research paper by renowned economists Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel, income inequality in India is at its highest level since 1922, the year the Income Tax Act was passed. In December, they will release the first ‘World Inequality Report’ where they will compare India’s inequality trajectory with other emerging, industrialised and low-income countries and suggest ways to tackle global and national inequality.

In an e-mail interview, Lucas Chancel discusses the findings of the paper titled ‘Indian income inequality, 1922-2014: From British Raj to Billionaire Raj?’ Excerpts:

Can you summarise key findings of the paper?

According to our benchmark estimates, the share of national income accruing to the top 1% income earners is now at its highest level since the creation of the Indian Income Tax [Act] in 1922. The top 1% of earners captured less than 21% of total income in the late 1930s, before dropping to 6% in the early 1980s and rising to 22% today. Over the 1951-1980 period, the bottom 50% group captured 28% of total growth and incomes of this group grew faster than the average, while the top 0.1% incomes decreased. Over the 1980-2014 period, the situation was reversed; the top 0.1% of earners captured a higher share of total growth than the bottom 50% (12% versus 11%), while the top 1% received a higher share of total growth than the middle 40% (29% vs. 23%). These findings suggest that much can be done to promote more inclusive growth in India.

You have said the income inequality has been at the highest level?

Since the 1980s, India did not only open-up and liberalise its economy, it did it in a way that was very favourable to top income earners and capital owners.

Top tax rates which were very high in the 1970s (up to 98%) decreased to 30% in the 1980s. Wages set by governments in government enterprises were liberalised after privatisations and the dispersion increased.

It is also likely that privatisations principally benefited richest income groups, those who already had capital, rather than the majority of the population which didn’t access equity.

On the other hand, growth at the bottom of the distribution was notably lower than average growth rates since the 1980s.

Is this finding unique for India?

To better understand the rise in Indian inequality, let’s look at other emerging countries. China also liberalised and opened up after 1978, and in doing so, experienced a sharp income growth as well as a sharp rise in inequality.

This rise, however, stopped in the 2000s so that inequality is currently at lower level there than [in] India (top 1% income share at 14% versus 22% in India, according to our estimates). In Russia, the move from a communist to a market economy was extremely brutal and today has a similar level of inequality as in India. This shows that there are different strategies to transit from a highly regulated economy to a liberalised one. In the arrays of possible pathways, India pursued a very unequal way but could probably have chosen another path. All this data is available on an open-access website, WID.world.

There have been counter arguments to your thesis?

Some commentators argue that without extreme growth at the very top of the distribution, there wouldn’t have been high growth in India. There is, in fact, little evidence supporting this claim. The top 0.1% captured more total income growth as the bottom 50% since 1980. Would all income growth have disappeared if the situation had been reversed? We can also doubt this. The highest growth period in Western Europe, after the second world war, was also a period of equitable redistribution of the fruits of growth. Europe grew as a market economy but it was not a market society. It had institutions, rules, norms limiting the power of capital accumulation and of income concentration.

What do these findings mean for India?

There are many options and we do not claim to put an end to debates. Regarding rising inequality at the very top of the distribution, we show that after 1980, in India, top Income Tax rates were brought from extreme levels to much lower ones. Land concentration is also an issue in India. where agriculture remains a key sector. Indeed, access to free and quality education and health is crucial to raise bottom 50% incomes.

Source: The Hindu

Leave a Reply