Real wages have risen across India in the past two decades, but the increase has been especially marked among rural unskilled workers. Three drivers — falling rural female labour force participation, a construction boom, and favourable agricultural terms of trade — help explain why unskilled rural workers fared better than their urban counterparts or workers with more education. Going forward, in the light of lower agricultural prices and slower growth in the construction sector, some of the factors that contributed to the increase in relative wages for unskilled labour during this period may not be sustained over time.

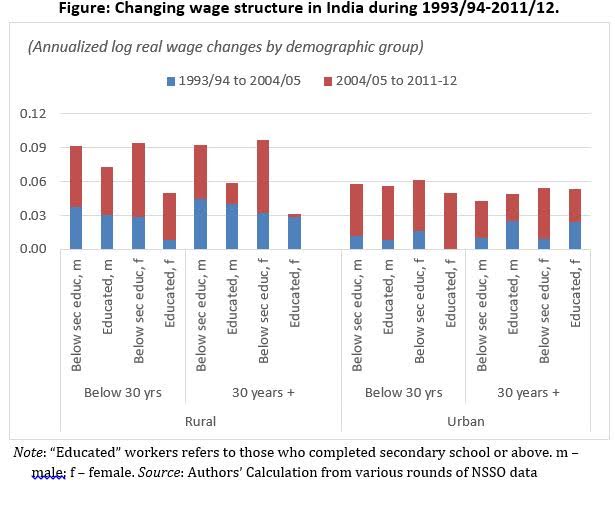

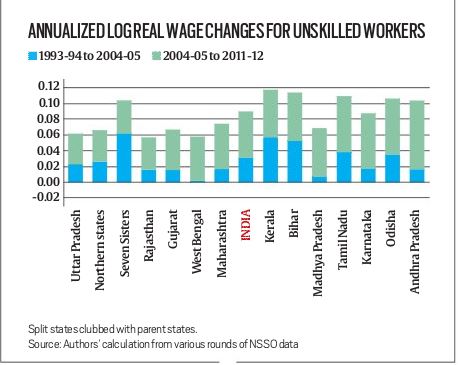

Over the last two decades, India’s workers have seen their wages rise substantially relative to the cost of living. Although real wages have risen across all of India and for all demographic groups (educated/uneducated, old/young, male/female), the rise has been especially marked among rural unskilled workers — those with less than full secondary education. This was particularly so between 2004-05 and 2011-12. While this phenomenon helps explain the fall in rural poverty during this period, it begs the question: what were the economic forces that drove the rise in real wages during this time?

To answer this question it helps to narrow it, by shifting our gaze from the overall rising tide of higher real wages nationwide, and asking instead why some ‘boats’ have risen faster than others — for example, why the wages of rural workers lacking secondary education (concentrated in sectors like agriculture and construction) have risen faster than those of their urban counterparts. Here are three key findings on how the relative wages of different groups changed between 2004-05 and 2011-12:

First, an expanding construction sector stands out as the key driver of relative wage growth for unskilled men. States in which the rural construction sector grew faster than the urban construction sector, such as Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka, saw faster relative wage growth for men with less than complete secondary education. What this means is that the wages of these men grew faster in rural areas of the state than in urban areas. There is no such effect on women’s wages. In contrast to the construction sector, relative growth in services, such as wholesale and resale trade, is unrelated to relative wages for either males or females.

Second, falling female labour force participation has played a role in helping raise wages, but only for women. States in which rural women withdrew from the labour force faster than urban women experienced a bigger rise in the wages of rural unskilled women. This pattern is essentially absent for males, suggesting that women’s unskilled labour is not a very close substitute for that of men.

Third, states that grew crops whose prices rose more sharply during the 2004-05 to 2011-12 period saw rural wages for unskilled labour, both male and female, rise faster than urban wages. Thus, against the backdrop of the overall decline in agricultural employment in India, states that benefited from the agricultural commodity boom saw a greater demand for farm labour, and hence rising wages for unskilled farm work.

While we cannot run a statistical ‘horserace’ to find the dominant force behind the recent changes in India’s relative wage structure, these three drivers do help us understand why unskilled rural workers have fared better than their urban counterparts. Going forward, in light of the recent moderation in agricultural prices and slower growth in the construction sector, it is already clear that some of the factors that contributed to the increase in relative wages for unskilled labour during this period may not be sustained over time. As a matter of fact, the rate of growth in real wages has slowed over the past few years, with potential implications for the pace of poverty reduction in the country.

These findings are based on a standard decomposition of wage growth into growth due to supply shifts (changing group employment shares), growth due to demand shifts (changing industrial composition biased for or against a particular group), and growth due to wage-premia shifts (essentially, movements into or out of structurally low-paying jobs). The portion of relative wage growth attributable to these three factors can then be extracted for each state, or groups of smaller states, and finally correlated with various economic changes at the state level. The key findings represent statistically significant correlations.

Source: The Indian Express

Leave a Reply